Prologue

This is the story of Mercedes-Benz, one of the world’s oldest and most luxurious car companies, worth around $80 billion. But being among the most desired and expensive cars today, it’s easy to forget its humble beginnings. It all started with a poor engineer who faced many doubts and failures in his pursuit of building the first horseless carriage. Despite his challenges, he proved everyone wrong and turned his small venture into the world’s first and biggest production car company during the late 19th century.

What began as an inspiring success story took a surprisingly dark turn when the company profited from supplying military vehicles to the Nazis, under the work of forced laborers. So sit back and relax because today we’ll be covering the insane story of Mercedes-Benz and the man who brought automobiles to life.

Humble Beginnings

Carl Benz was born in November 1844 in the German town of Mühlburg. Born into a low-class household, his father was a locomotive driver who barely managed to sustain the family. However, when Carl turned two years old, his father passed away, leaving him and his mother in dire financial straits. Benz’s childhood wasn’t easy. Despite living in poverty and going to bed hungry, his mother did everything she could to ensure her son received a good education. Thanks to her efforts, Carl attended school and showed signs of brilliance at a young age, particularly in chemistry and mechanics.

By the age of 15, Carl decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and passed the entrance exam for mechanical engineering at the University of Karlsruhe. He met a teacher who would significantly impact his life there: Ferdinand Redtenbacher. Redtenbacher, regarded as a pioneer who transformed mechanical engineering into a technical science in Germany, believed steam engines—then mostly used for railways and boats—were becoming obsolete. Under his guidance, Carl’s interest in horseless carriages began to grow. As a regular bicycle rider, Carl started tinkering with his bike, exploring ways to create a motorized vehicle.

By then, several engineers and inventors had attempted to build automobiles, and while a few succeeded in creating self-propelled vehicles, these early models were impractical. Carl noticed that most of these vehicles relied on steam engine technology, which he realized was not the future, and under Redtenbacher’s guidance, Though many laughed at his vision, Carl remained determined. He just needed more time to prove it. After graduating from Karlsruhe at 19, Carl spent the next seven years working various engineering and construction jobs. Though he struggled to fit in, he used these experiences to launch his venture in 1871 at the age of 27.

Carl partnered with mechanic August Ritter, and together they started an iron foundry and mechanical workshop in Mannheim. At the same time, Carl continued working on his side project: developing a motorized carriage. However, Ritter proved to be an unreliable partner. After local authorities impounded their tools, the company faced severe financial struggles in its first year. Fortunately, Carl had met Bertha Ringer around this time. Born into a wealthy family, Bertha shared Carl’s strong values and couldn’t bear to see his efforts wasted by his partner. She used her dowry to buy out Ritter’s share, giving her and Carl full control of the business.

Together, Carl and Bertha turned the situation around, keeping the business afloat for the next 10 years. During this period, Carl’s genius truly emerged. He made significant breakthroughs, most notably developing a gasoline-powered two-stroke engine in 1879. To generate more revenue, Carl patented his inventions, including an engine speed regulation system, battery ignition, spark plug, carburetor, clutch, gearshift, and water radiator. These designs not only brought Carl closer to achieving his dream of a horseless carriage but also expanded the range of products his business could offer.

However, the business faced challenges. Rising production costs forced Carl to incorporate the venture, leading to the involvement of external investors. By 1882, his company became a joint-stock corporation, leaving Carl with only 5% ownership. Stripped of authority and excluded from major decisions, Carl grew frustrated. His ideas were no longer considered, and he had no say in the company’s operations. Hurt and disillusioned, Carl eventually packed up his belongings and left the corporation.

Benz & Cie

Leaving his company was a hard blow for Carl, but the disappointment made him even more determined to succeed. His passion for bicycles brought him into contact with Max Rose and Friedrich Wilhelm, two men who owned a bicycle repair shop in Mannheim. Together, they established Benz & Cie., focusing on manufacturing industrial machines and stationary gas engines. Unlike Carl’s previous venture, this one started well and became profitable in a short time. With steady income flowing in and a staff of 25 people, Carl was finally able to focus on his lifelong dream: building an automobile.

Instead of simply adding a motor to a carriage, Carl designed the carriage around the motor. Using technology similar to that of a bicycle, he constructed what many consider to be the first true automobile in 1885: the Benz Patent Motorwagen. This two-seater vehicle ran on three wire wheels, forming a tricycle, and was powered by a gasoline four-stroke motor. Its one-cylinder engine produced 2/3 of a horsepower and could reach a top speed of about 7 mph. Carl knew this was revolutionary. After testing and refining his vehicle, he publicly unveiled it in the summer of 1886.

The reception, however, was mixed. While some admired Carl’s invention, many were skeptical. Critics doubted the safety of the machine, fearing it might explode. Some people even believed Carl was the devil driving an “infernal carriage.” His business partners were equally unimpressed. They saw his obsession with the automobile as a distraction and couldn’t fathom why anyone would buy such a machine. “It’s no quicker than a horse,” they argued, “it can break down easily, and it can run out of fuel.”

Despite the skepticism, Carl was convinced that his horseless carriage was the future. He began manufacturing cars for sale in 1888, becoming the first person in the world to do so. His wife, Bertha, was his biggest supporter. She often stayed with him in the workshop. offering suggestions for improvement. However, even after making enhancements, the public remained unconvinced. The few who bought the cars found them impractical—they could only cover short distances, required constant attention from mechanics, and were prohibitively expensive.

The vehicles were accessible only to the wealthy elite, and even they were reluctant buyers. The cars were loud, messy, and inconvenient, further hindering their appeal. It became clear that Carl needed to convince the world that the automobile was here to stay.

The Trip That Shaped The Future

One morning in the summer of 1888, Bertha Benz got up early while Carl was still asleep, hopped into her husband’s car, and embarked on one of the most important journeys in automobile history. She brought along her two sons and set out to visit her mother in Pforzheim, 66 miles away from Mannheim. Bertha did not inform her husband or the authorities about her plans, likely knowing they would try to stop her. At the time, no motorized vehicle had ever attempted such a long journey, but she was determined to prove the value of Carl’s invention.

Her trip, however, was far from easy. Bertha faced numerous challenges along the way, including navigating dusty, stony roads meant for horse-drawn carriages, stopping at a pharmacy to purchase more fuel, and even performing mechanical repairs herself. Despite these obstacles, the 66-mile trip took Bertha and her sons over 12 hours to complete, but they eventually arrived safely in Pforzheim. The journey achieved exactly what Bertha had hoped: it drew attention to the automobile and demonstrated its potential as the next big thing.

The Benz Patent-Motorwagen became the talk of the town and brought significant publicity to Carl’s business. Soon, Benz & Cie. began expanding rapidly. By 1890, it had become Germany’s second-largest engine manufacturer—not by selling cars, but by producing stationary gasoline engines. However, the addition of two new business partners, Friedrich von Fischer and Julius Gans, transformed the company. They managed the business and marketing side, allowing Carl to focus on engineering. This enabled Carl to patent several new automotive innovations, including the planetary gear transmission, double-pivot steering, and a flat engine with a boxer configuration.

In 1893, at the recommendation of his business partners, Carl designed and manufactured an improved automobile, the Benz Victoria. This luxurious two-passenger vehicle featured a 3-horsepower engine capable of reaching speeds of 11 mph. The Victoria sold fairly well, but it was its successor, the cheaper Benz Velo, that truly revolutionized the market. With a production total of about 1,200 units, the Benz Velo became the world’s first mass-produced automobile, making Benz & Cie. The largest automobile company in the world during the 1890s and early 1900s.

However, as the Benz company celebrated its newfound success, it faced growing competition from another nearby firm: Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft. This rivalry would mark the beginning of the next chapter in the history of the automobile.

The Rivalry

Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) was headed by Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach, both brilliant engineers. Gottlieb Daimler, in particular, was known for being highly competitive and having extensive connections and business acumen—qualities Carl Benz seemed to lack. The first Daimler car to be sold commercially appeared in 1892. Two years later, they followed it with a two-cylinder model, and in 1897, they introduced their first front-engine vehicle, the Daimler Phoenix. It became clear that Daimler’s company was catching up to Benz, as their vehicles were more appealing and comfortable for the public.

Unfortunately, Daimler passed away in 1900, leaving Maybach in charge. Under Maybach’s leadership, the company created the Mercedes 35-horsepower in 1901, a groundbreaking vehicle. This car resembled the modern idea of an automobile, featuring a powerful gas engine, a wider and larger body, a steel chassis, and a low center of gravity. Initially built for racing, it was commissioned by wealthy businessman Emil Jellinek, who named it after his daughter, Mercedes. The car achieved speeds of up to 56 mph, making it far superior to other vehicles of its time. Winning multiple races, the Mercedes 35-horsepower drew massive attention, prompting Daimler to rebrand all their vehicles under the Mercedes name and produce new models for both racing and public use.

Meanwhile, this rising competition troubled Carl Benz’s partners, who sought to respond with a faster model. Without Carl’s approval, they hired French designers to help develop a competitive vehicle. Carl, who disliked auto racing and preferred slow, careful driving, was upset by this decision. The resulting car was not a success, further damaging the Benz company during crises between 1903 and 1904. Disappointed, Carl stepped back from active involvement in the company, though he remained on its board of directors. Eventually, the decision to allow Benz cars to race paid off, and the company’s racing successes helped save it.

By 1908, Benz introduced a 120-horsepower racer that completed the journey from Leningrad to Moscow in 8.5 hours at an average speed of 50 mph—an incredible feat given the poor condition of roads at the time. The 1909 Benz 200-horsepower “Blitzen Benz” went even further, breaking the absolute speed record for any vehicle of its era, reaching over 140 mph by 1911. These achievements placed Benz alongside Daimler as one of the most desired car manufacturers of the time, with both companies enjoying strong sales in the years that followed.

However, the outbreak of World War I brought significant challenges. Germany’s defeat and subsequent economic recession left both Daimler and Benz struggling to survive. In 1924, the two companies set aside their rivalry and signed an agreement to combine production and marketing efforts while retaining their names to cut costs. But as the German economy worsened, they merged completely in 1926 to form Daimler-Benz.

Under Daimler-Benz, the newly branded Mercedes-Benz vehicles gained significant acclaim. The late 1920s saw the release of several impressive models, such as the Mercedes-Benz Type 630 and the S, SS, and SSK models. One of the key engineers behind these vehicles was Ferdinand Porsche, whose name would later become legendary in the car industry.

Carl Benz, meanwhile, remained on the Daimler-Benz board of directors. He lived to witness the tremendous success of his automobiles and marveled at how far the auto industry had come during his lifetime. Carl Benz passed away in April 1929 at the age of 84. After his death, the company continued to grow, becoming one of the world’s leading performance car manufacturers and experiencing some of its best years under unexpected leadership in the years that followed.

A New Direction

when Hitler Rose to power in Germany in 1933, he wanted to Showcase German engineering and Technology to the world, hoping to elevate his political standpoint above those of his contemporaries one way he decided to impress the world was by exhibitingGerman cars in international Motorsports almost immediately he provided big subsidies to Daimler-Benz enabling the company to heavily invest in Grand Prix racing, unlike any other car manufacturer of the time. From 1934 to 1939, Mercedes dominated these races, reaching speeds of up to 200 mph with their W25 and W125 models. However, they faced a strong competitor in Auto Union, another German automaker supported by the government. Auto Union also enjoyed significant success during this period, winning 25 races between 1935 and 1937. These achievements positioned Germany as a leader in motorsports, with Mercedes-Benz becoming a symbol of national pride and even Hitler’s preferred car brand. One of the vehicles he frequently used was the Mercedes-Benz 770, a luxury model primarily reserved for high-ranking Nazi officials.

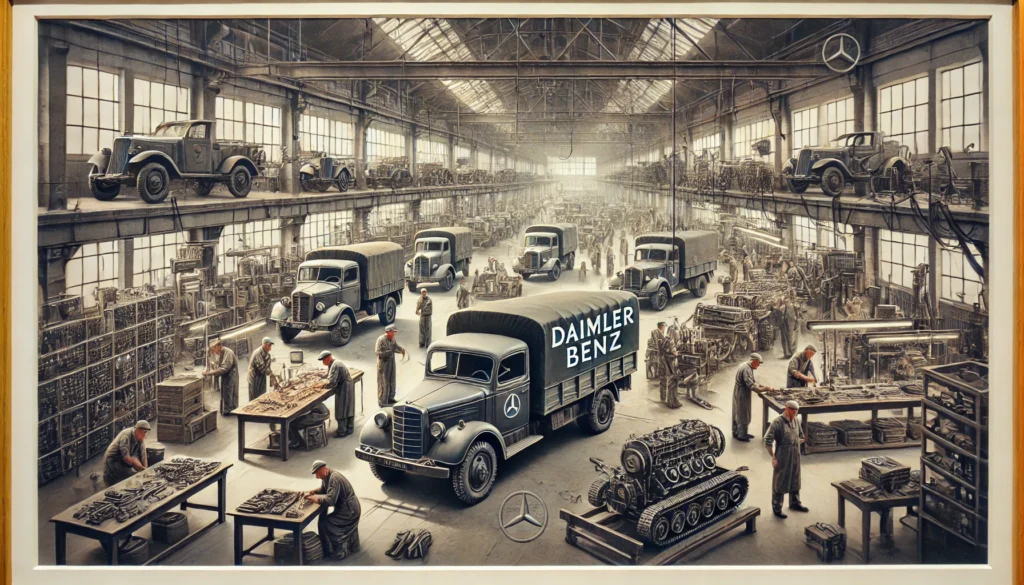

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Daimler-Benz faced a new challenge as civilian passenger car demand plummeted. The company pivoted to producing military vehicles, submarines, tanks, and aircraft engines for the Nazi war effort, with their military trucks being their most prominent line. By 1942, civilian car production ceased entirely, as all resources were redirected to armor manufacturing. With much of the male workforce on the front lines, Daimler-Benz began recruiting women to fill the labor gap. However, this was insufficient to meet demand, leading the company to rely on forced labor.

Prisoners of war, abducted civilians, and detainees from concentration camps were coerced into working under harsh conditions. Many were housed in barrack-style camps with prison-like conditions, while concentration camp detainees faced even more inhumane treatment under SS supervision. Severe malnutrition, mistreatment, and torture led to many deaths. By 1944, nearly half of Daimler-Benz’s 63,000 employees were forced laborers, most of whom came from Eastern Europe.

After the war ended in 1945, Daimler-Benz suffered immense losses due to the Potsdam Agreement, which required all German assets abroad to be confiscated and used for reparations. This stripped the company of its foreign subsidiaries, affiliates, and branches, forcing it to rebuild from its remaining domestic plants. Restructuring efforts included “denazifying” its top management, which helped the company secure a production permit from American occupation authorities in 1946. Despite significant bomb damage to its factories, Daimler-Benz had the advantage of retaining ownership of its plants, unlike competitors like BMW, whose facilities ended up in Soviet-controlled territories.

Mercedes-Benz initially focused on producing ambulances, police vehicles, and delivery vans based on their 170V models, using one plant as a repair facility for U.S. military transports. By 1947, the company resumed passenger car production, although only 1,045 units of the 170V were produced that year. Remarkably, Daimler-Benz turned a profit just one year later.

In the 1950s, Mercedes-Benz regained its influence, staging a strong comeback in motorsports and achieving significant global sales success. By 1954, the company had profited over a billion dollars, cementing its position as one of the world’s most valuable car brands. None of this would have been possible without Carl Benz, who, despite his humble beginnings, challenges, and critics, demonstrated the courage and determination to turn his vision into reality.